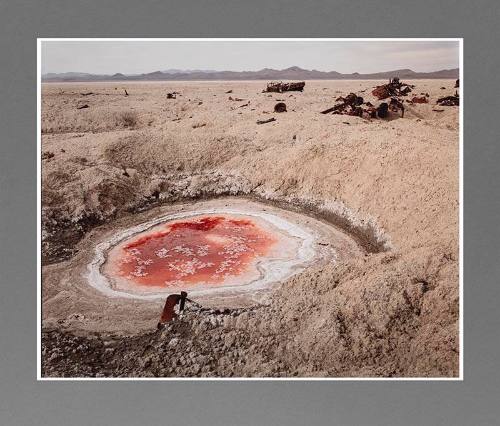

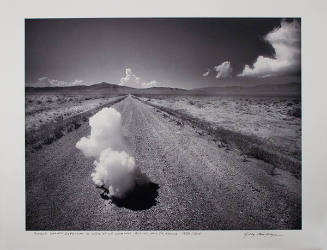

Bomb Crater and Destroyed Convoy, Bravo 20 Bombing Range, Nevada

Support: 29 5/8 × 37 1/2 in. (75.2 × 95.3 cm)

Mat: 36 × 42 in. (91.4 × 106.7 cm)

Text Entries

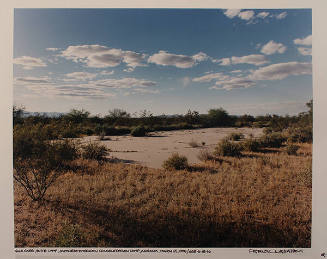

Richard Misrach (American, b. 1949) is one of the foremost landscape photographers of his generation and for decades his work has been an important part of the dialog about land use in the west. The museum owns no work by this important artist and this proposed acquisition is meant to correct that, with the idea that the museum’s collection should reflect not only the central artists in the history of photography but also include work that addresses the central issues of the region in which it is situated. Despite his importance, Misrach’s work is scarce in New Mexico collections. The Art Museum at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque owns three early works by the artist, all acquired in the 1980s: Saguaro #3, 1979; Sounion, Greece II, 1979; and View from Travertine Rock, 1984

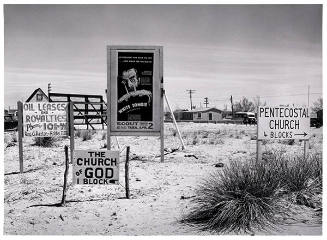

Misrach was studying psychology in the late 1960s at the University of California at Berkeley when he became interested in photography. The campus ran a non-credit photography program known as the ASUC Studio, where students could use the darkroom for free. Looking to try something new, Misrach and anthropology major Steve Fitch got interested in night photography and the use of strobes. Misrach used them in the wee hours to illuminate the denizens of Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue and the desert landscape, the former published as Telegraph, 3 A.M. in 1974 and the latter premiered with an exhibition and catalog in 1979. Misrach soon switched to color film and continued working in the desert, creating images of a variety of events in that landscape, including fires, trains, space shuttle landings, and a series on the Salton Sea in California.

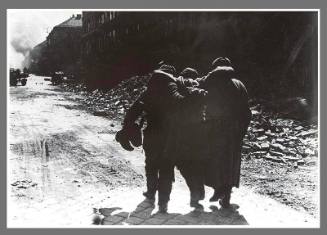

Misrach’s work from 1979 onward are organized into suites of images he calls Cantos. Each canto is independent but is also connected, visually and conceptually, to the others, forming an accumulation of meaning. A central theme in all of them is the collision between nature and culture. “My main problem with [Ansel] Adams’s perfect unsullied pearls of wilderness and his followers is that they are perpetuating a myth that keeps people from looking at the truth about what we have done to the wilderness,” Misrach told the photography curator Anne Tucker in 1996. By the mid-1980s, Misrach’s work was becoming increasingly politicized as he was making pictures in the Nevada desert of toxic waste, large pits of dead animals, and abandoned bombing ranges, many of which became Canto V: The War and Canto VI: The Pit.

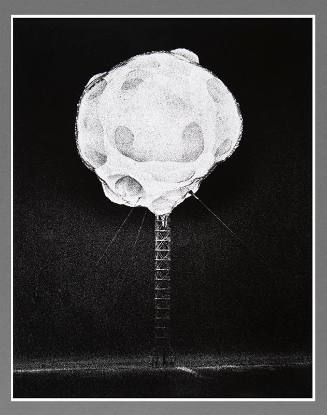

Misrach discovered that well after the conclusion of World War II, the U.S. military continued to use an area in the Carson Sink of northwestern Nevada (also the location of a sacred site for the region’s Northern Pauite people), as a bombing range. Known as Bravo-20, the site bears the scars of routine bombing and dumping of toxins including napalm and jet fuel. His research on the American West as a site of covert, illegal, and life-threatening experiments also led him to the disturbing spectacle of a pit of hundreds of dead animals in Nevada. The volume of bodies suggested that hot spots of hazardous material had contaminated the area’s livestock and agriculture.This work carried additional resonance in light of the accident the nuclear plant at Chernobyl in 1986, which underscored that the negative effects of nuclear power and testing were not confined to the 1940s and 1950s. Misrach’s potent photographs eventually came to the attention of the Bureau of Land Management, who contacted the Bureau of Reclamation and initiated an investigation.