The Pueblo Revolt of 1680

eMuseum Notes

In 1680, the Pueblos united in revolt to expel the Spanish from their territory. Organized by the holy man Popé of Ohkay Owingeh, the Pueblos coordinated the revolt by using a knotted rope, with instructions to untie a knot each day until the last knot was undone and the attack began. The Pueblos succeeded and regained their religious and economic autonomy for eleven years until the Spanish returned.

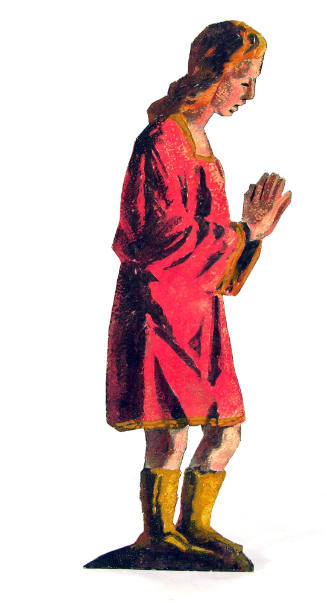

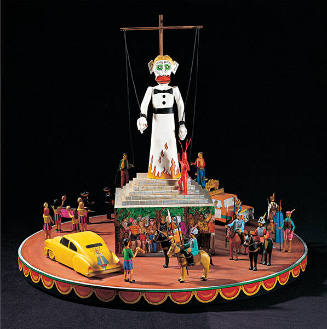

In recent decades, historians and artists alike have assessed the significance of the insurrection, and artist Paul Moore interpreted it as a hallowed event in his Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Moore, as an act of reverence, combined iconography associated with the revolt and with Spanish Catholicism. Within a niche framed by ornamental tin work, a Spanish man of the seventeenth century is bound and pierced by two arrows, a visual treatment resembling images of Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom. Moore used the form of the bulto, a religious sculpture often depicting Catholic saints, as a reference to the Spanish killed in the Pueblo Revolt in service to both the Spanish empire and the Catholic church.

The rope, both knotted and untied, appears throughout the piece and the Zia sun symbol, which would become the flag of the future state of New Mexico, serves as a halo, though ringed by the names of the Pueblos that participated in the revolt. Moore’s representation honors the revolt as a pivotal moment in Pueblo self-determination, while also acknowledging the tragedy that accompanied Spanish expansion into North America.

- Pueblo

- popes

- Zia

- colonization

- arrows

- deaths

- bultos